It’s the first thing poultry farmers in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley think about in the morning, and the last thing they worry about at night, according to industry spokeswoman Amanda Brittain.

The threat is avian flu, which has resulted in the deaths of millions of birds from infection or culling, and has become a pervasive fear for farmers as infections spread, said Brittain, chief information officer with the BC Poultry Association.

She said the industry has placed itself on level “red” – the highest of three levels – in its biosecurity program as farmers fight to fend off the outbreaks, which have been triggered by migrating wild birds.

“Before anybody goes into the barn, they’re changing their shoes two or three times,” said Brittain.

“They’re changing their clothing or putting on a biosecurity suit over their clothing. Extra precautions are taken to disinfect any vehicles that come on and off the farm, that sort of thing, because the virus is in the environment.”

Canadian Food Inspection Agency data show there have been 39 B.C. outbreaks of H5N1 avian flu since Oct. 20, resulting in almost five million birds dying of infection or being “humanely depopulated” to halt the spread of the virus.

The agency said in a statement that 34 premises had been infected in B.C. this month, 33 of them commercial poultry operations in the Fraser Valley.

The potential threat is not restricted to the poultry industry.

Provincial health officer Bonnie Henry this month urged poultry workers to get their flu shots, since there is concern that a rare human infection of avian flu could cause the virus to mix with human influenza and mutate into something more contagious among people.

Such a development has long been feared among scientists worried about where the next pandemic illness will come from.

Agriculture Minister Pam Alexis said the province has been working with farmers and the CFIA on preventing the spread of avian flu, including a $5-million program launched in the spring to help improve biosecurity at farms.

But Alexis said the risks of avian flu spreading locally is always present because the Lower Mainland and the Fraser Valley are on the Pacific Flyway, a major north-south path for migratory birds in North America.

“It’s migratory birds that defecate on or close to farms,” Alexis said. “And that’s brought in through various means, perhaps through the workers or the birds themselves.

“This is the reality that we’re living in right now, and so prevention and preparation is really the key.”

BC United MLA Ian Paton, who is also the shadow minister for agriculture, said the NDP provincial government should be doing more.

“This means listening to the concerns of our poultry producers, rapidly providing them with the necessary resources and support, and implementing strategies to prevent further outbreaks,” Paton said in a statement.

Brittain likened the situation to another COVID-19 pandemic for farmers, who have now isolated themselves from each other to avoid spreading H5N1, resorting to Zoom and other online platforms to meet and discuss how to handle the outbreaks.

Physical visits to farms are extremely limited, with only feed trucks, egg pickups and veterinary visits being allowed, Brittain said.

“Almost no one goes into the barn other than the farmer themselves or a vet,” she said.

She said that because chickens in a barn could not be separated, “we need to protect them by trying to stay away from other farms.”

“No farmer is going to visit other farms right now and then going back to their home farm. That’s not happening.”

The situation is similarly dire among wild birds.

The Wildlife Rescue Association of BC, a non-profit animal rescue group, said it had received at least 100 calls from the public since Oct. 1 about sightings of possible infected wild birds, showing symptoms such as the inability to stand or fly.

Association support centre manager Jackie McQuillan said the situation was straining the group’s 20 or so full-time staff and 200 volunteers.

McQuillan said most infections were among geese and ducks, although other birds can also be infected. The CFIA says H5N1 has been “sporadically detected” in Canada in mammals including raccoons, skunks, foxes, cats and dogs.

McQuillan said the number of avian flu cases was putting everyone and the association’s finances under duress.

“When you think about all of the extra personal protective equipment that’s required, the extra mileage that people are spending to drive out to the outlying areas for rescues, the extra time that we spend on the phone fielding and managing those calls, (it) has definitely been a massive strain on our organization,” she said.

Brittain said the most difficult part for some farmers is that they recently had to deal with another source of catastrophic loss, the 2021 atmospheric river flooding that killed about 630,000 chickens in the Sumas Prairie.

But despite the difficulties, Brittain said no one in the industry has expressed a desire to exit the sector.

“Farming is a lifestyle,” she said. “It’s not a job. They do this because they love it. They love taking care of animals, which is why it hits them hard when they lose the flock to a disease. But they want to keep doing this job.”

‘Stress and anxiety levels are off the charts’: Dozens of B.C. farmers devastated by rise in avian flu outbreaks

More than 30 farms in B.C.’s Fraser Valley have tested positive for avian flu, also known as bird flu.

“Stress and anxiety levels are off the charts,” said Amanda Birttain, spokesperson for the B.C. Poultry Emergency Operations Centre. “Since Oct. 20, we’ve had 36 infected farms and we do not see an end in sight yet.”

Brittain calls the recent spike the worst she’s seen in her twenty years working in the industry.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) told CTV News that five million birds in B.C. have either died or been euthanized since the first case in the province in April 2022.

“Primary Control Zones (PCZs) have been established in the 10 km surrounding each of the infected premises,” said the CFIA in an email to CTV News. “Disease surveillance is done within the PCZ to determine if there has been any disease spread and mitigate the risk of infection at other premises.”

When avian flu is detected at a farm, all birds are euthanized in order to prevent further spread of the disease.

“Watching friends of mine lose their birds is heart-wrenching,” said Juschka Clarke, an egg farmer from Chilliwack.

Clarke says she knows of a handful of farmers who’ve had to euthanize their entire flock and start from scratch. She adds that the emotional and financial toll can be devastating.

“Our stress level’s pretty high right now. We pride ourselves in keeping our birds healthy and happy,” said Clarke. “We’re watching farmers struggle hard.”

Clarke says she’s started taking extra precautions to try and keep her farm safe.

“Everybody’s had heightened biosecurity, meaning that we don’t allow a lot of traffic on and off our farm.”

In addition to birds, other animals including skunks and foxes have tested positive for the virus.

Pets can also be vulnerable if they eat or come in close contact with a sick or dead bird infected with the disease.

The risk for humans is considered very low.

“The humans who have ever caught influenza have had prolonged exposure to sick or dying birds, so you don’t have to worry about driving by a farm or catching anything,” said Brittain.

Brittain says despite the concern for farmers and high numbers of birds killed and euthanized, overall poultry supply remains stable. She adds that as of right now, she doesn’t expect avian flu to impact the price of poultry.

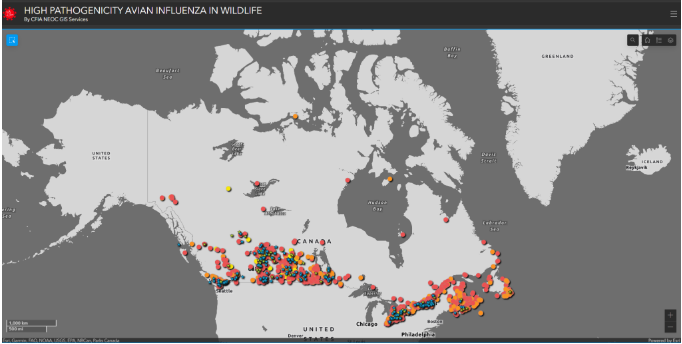

Cases of avian influenza are increasing across Canada, government data shows, but a lack of monitoring of wild birds is underscoring the threat to humans, experts say.

Also known as the bird flu, the subtype H5N1 spreads rapidly in poultry farms due to densely populated coops. However, wild birds are being disproportionately impacted by the virus.

As of Nov. 2, approximately 7.9 million poultry birds have been impacted in Canada this year,(opens in a new tab) the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) website shows.

British Columbia has the highest number of birds impacted, followed by Alberta and Quebec.

The high spread rate of the virus is causing a particularly bad year for avian flu, experts say.

Not included in that total is the estimated 2,500 wild birds that have tested positive or are suspected to be positive for avian influenza(opens in a new tab), according to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative.

Influenza is deadly for poultry birds not because of the virus itself, experts say, but because of the policy around the flu in coops.

When a poultry bird has contracted a highly transmissible subtype of avian flu, all birds that have come in contact with the animal will be killed to prevent further spread(opens in a new tab), the CFIA website reads.

But with cases in wild birds, transmission is not so strictly controlled. The virus often spreads without being checked, and some experts warn it is already mutating to infect other species.

“The more the virus is allowed to circulate, the more it’s allowed to evolve and change,” said Jennifer Provencher, a research scientist in the Ecotoxicology and Wildlife Health Division of Environment and Climate Change Canada.

“This particular H5N1 is a different beast than the previous ones that we have encountered,” she told CTVNews.ca in an interview earlier this week.

BIRD FLU SPREAD IN CANADA

The latest subtype of avian flu is unlike any other scientists have seen in Canada, Provencher said.

“The H5N1 has caused such widespread mortality that I think we can pretty confidently say that within living memory, no avian influenza has affected wild birds in the same capacity,” she said.

“Just like humans, as the birds congregate on the landscape during migration, they pass it to each other – just like we would pass the flu to each other. When they go into their kind of nesting zones, they spread out in the landscape, and that transmission stops,” she said.

Typically the bird flu has seasons just like human influenza does, Provencher said.

A huge outbreak occurred this past spring. With cases rising in parts of Canada again, some experts say they’re preparing for another difficult season.

‘INFLUENZA IS STILL THE VIRUS WE NEED TO WATCH’

Bird flu was first detected in Canada in 2004, and has a history of mutating to subtypes that can easily infect humans, such as the subtype called H1N1, which transmitted from pigs and was also known as swine flu. The H5N1 subtype is the latest mutation, and is impacting wild birds in particular.

Currently, cases of humans catching H5N1 are extremely rare, with Health Canada data showing just over 800 people worldwide have contracted the virus since 1997.

H5N1 can infect more than just birds, with cases found in foxes, skunks, cats, dogs, bears and other mammals. This shows that the virus is mutating and infecting more than just birds, Joly said, and the more animals contracting the virus, the better chance humans have at interacting with it.

“Every time a human comes in contact with an infected animal, it’s like rolling a dice…if you roll your dice more often, you’re more likely to get the winning number, or in this case, you’re more likely to get transmission to human,” said Damien Joly, chief executive officer of the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative, a research organization in Canada.

“This is definitely why we’re all concerned about avian influenza in birds.”

“In 2005-06, avian influenza was not being sustained in the wild population, it would die out,” Joly told CTVNews.ca in an interview this week.

“But this bug we’re dealing with seems to be different. It may be because there are (many) species that it can infect, (and) we’re seeing the virus over winter now, which is something that we didn’t see (before).”

Due to the high transmission rates in wild birds and the virus infecting other animals, Joly said he believes avian influenza could make a more aggressive jump to humans.

“My whole career, I’ve always thought influenzas will be the next pandemic, I was adamant, and of course, I was wrong; COVID happened,” Joly said. “But look all the previous pandemics…Despite all this distraction about coronaviruses, influenza is still the viruses we need to be watching.”

In terms of who is most at risk right now of contracting H5N1, federal officials say it’s people who work with poultry, hunt wild birds or are in contact with birds that eat small mammals.

LACK OF SURVEILLANCE LEAVES QUESTIONS

To understand how the virus is mutating, tracking positive infections in wild birds and other mammals is key, Provencher said.

A dashboard from the Canadians Wildlife Health Cooperative provides some answers to where infections spread among wildlife

, but it’s only a snapshot of the thousands of animals that could have the virus, Joly said.

In an effort to provide more data, Environment Canada has “ramped up” surveillance of the bird flu over the last two years through antibody testing, Provencher said.

“This is giving us a peek into (wild bird) exposure in the last three to six months, and so that’s allowed us to figure out who’s been exposed (and if) we are building a herd immunity,” she said.

The work Provencher does is “tricky,” she said, because birds need to be tested for the virus the same way humans are: through a swab. This means catching, testing and releasing the bird.

“Just like COVID or the flu, you only shed the virus in this five- to seven-day window, so if you don’t have the bird in that exact five to seven days, they can test negative,” she said.

Since 2020, the program has swabbed more than 17,000 live and 10,000 dead or sick birds to get a better understanding of H5N1’s impact, Provencher said.

But funding pressure on government wildlife programs is a concern, she said. For scientists to understand the risks to animal species and humans, long-term monitoring and testing is needed, Provencher said.

“If we ramp down our ongoing surveillance, then we’ll have captured this big outbreak, but we won’t be able to understand whether some birds are becoming long-term reservoirs for the virus or if the virus is continuing to mutate into different subtypes,” Provencher said.

“The Centers for Disease Control across the world and the World Health Organization and the Organization for Animal Health, they’re all keeping an eye on it because it does have such implications for human health,” she said.

British Columbia’s provincial health officer is urging people living or working on the province’s poultry farms to “prioritize” getting influenza vaccinations as avian flu spreads among flocks this fall.

Dr. Bonnie Henry said while avian flu doesn’t transmit easily from birds to humans, infections are possible – creating a risk the virus will mutate into a more dangerous form.

“If we have somebody who gets infected with both the human and the bird virus, that virus can re-assort and create a new influenza virus that could be more infectious to humans,” said Henry at an update Friday on B.C.’s respiratory illness season.

“So that’s a risk that’s in the back of our mind all the time with these.”

That is why people connected to poultry farms are being asked to vaccinate against the human strains right away, she said.

Scientists and health officials around the world have long been concerned that a mutation of avian flu into a strain that is easily transmissible among humans could trigger a global pandemic.

Henry said at least 16 farms in B.C. have been affected by the latest avian flu outbreaks, with Canadian Food Inspection Agency data showing nine commercial infected zones, mostly in the Fraser Valley.

The number of infected flocks has grown dramatically in recent weeks, a development Henry said did not surprise officials.

She said health authorities are keeping a close eye on whether the return of migratory seabirds in the fall would bring about new outbreaks of avian flu, after spring migrations triggered the last cluster of outbreaks in the province.

“So far, globally, there’s been very little spillover infecting humans,” Henry said. “But it can happen.

“The risk of infection is low for most of us, given the limited contact we’d generally have with infected birds. But people like workers on poultry farms, farm families and others who have close contact with birds, (we) really encourage you to make sure you’re taking the appropriate precautions.”

The province said it has administered more than one million influenza vaccines and close to 850,000 COVID-19 shots since launching its respiratory immunization campaign in October.

Avian flu infects more B.C. farms as wild birds migrate overhead

Avian flu is spreading rapidly through British Columbia poultry farms, including half a dozen diagnosed in commercial flocks this week alone.

The fall migration of wild birds is considered the primary cause of infection for B.C.’s commercial and backyard operations.

B.C.’s chief veterinarian issued two orders last month to try to stop the disease from spreading, telling farmers to keep their birds indoors and stopping markets and auctions.

Since Oct. 20, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency shows there have been 16 confirmed cases of the highly virulent H5N1 virus.

The B.C. Agriculture Ministry says once a positive test is confirmed, the flock is quarantined, culled and then disposed of.

The ministry says farmers need to remain vigilant despite the preventative measures put in place, and any sick or dead bird should be reported through the province’s wild bird surveillance hotline.